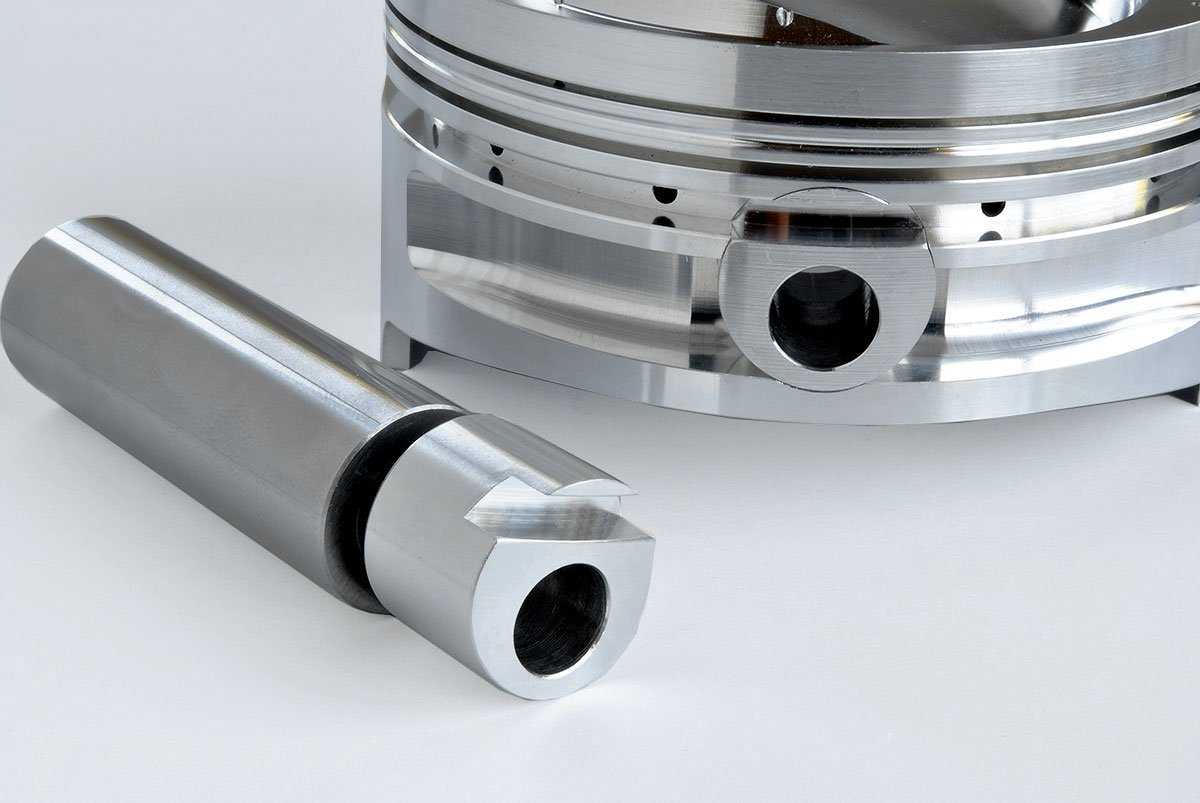

Wrist Pin Locks: Different Styles and How To Install Them

There are many ways to adhere the piston to the connecting rod and each have unique pros and cons. Here’s a look at different piston lock types and how to correctly install them.

Ask experienced engine builders to identify the most frustrating or aggravating step in the assembly process, and the likely consensus will be installing any style of those temperamental spring-loaded wrist-pin locks. They’re inexpensive, considering the workload placed on them, but these locks are crucial to an engine’s durability. If they fail, then any number of scenarios can follow, almost all of them catastrophic. To swear that these gruesome instruments of torture are cursed is not a sin. Yet, we must understand them to love them.

Let’s start with a few basics. There are three methods of attaching a piston to a connecting rod:

- Anchored or fixed pin—The wrist pin pivots freely within the little end of the connecting rod, usually with the help of a bushing. The piston is locked to the pin using screws that go through the pin bosses into the pin. This method is used mostly in industrial engines and never seen in the performance market, unless perhaps a rare vintage application.

- Semi-floating pin—The pin is secured to the connecting through some form of friction, then the piston pivots freely within the piston pin bosses. Securing the pin to the rod is usually accomplished by press-fitting. The little end of the connecting rod is heated, which expands the metal and the diameter of the hole. The piston is positioned over the rod, and then the pin is pressed into place. Another way to hold the pin to the rod is with a “cinch-bolt” connecting rod design. Here, the small end is split, allowing the pin to be positioned, and then it is secured in place when the cinch bolt on the rod is tightened. This design is pretty much exclusive to large industrial engines where there’s enough room to get a wrench up inside the piston.

- Full-floating pin—The pin pivots freely within both the little end of the connecting rod and the piston pin bosses. The wrist pin is held in check and kept from scratching the cylinder by one of two methods:

- A spring-loaded lock on each side that secures the pin between the pin bosses (this can be a spirolock, circlip, round-wire lock, etc.

- A pair of buttons that take up the space between pin and cylinder wall, keeping the pin centered in the pin bosses.

Semi-Floating

The press-fit semi-floating pin is prevalent in production engines, especially older models, while most high-performance engines use full-floating pistons.

“Press- fit pins require the rod to be heated, which is bad for the rod material from a heat-treat standpoint. Pressing requires equipment that floating pins do not,” explains Alan Stevenson. “There’s difficulty of assembly and disassembly. Also, floating pins are naturally centered in the piston, which assures even loading. It’s a pain to perfectly center a pressed pin.”

On the downside, free-floating pistons require those nasty locks. But hardly any solution is achieved without some complication. The majority opinion about wrist-pin locks is that they solve more problems than they create. But what about pin buttons? They’re as easy to install as pushrods.

Pin Buttons

“Buttons are popular in certain classes of drag racing, due to ease of assembly and disassembly, such as between races in Top Fuel. Outside of drag racing, a lot of people don’t even know about them,” says Stevenson, adding that buttons are also considerably more expensive than locks. “On the downside, buttons are free to rotate and therefore are not considered the best solution for supporting the oil ring when the pin hole intersects the oil ring groove. Buttons are also heavier.”

Pin buttons have also earned a sour reputation for wiping oil off the cylinder wall and possibly scoring the metal surface—or at least scraping the oil in that location and allowing grit or carbon buildup to dig into the wall. They’re best left to applications where the engines are serviced frequently.

Wrist-Pin Locks and Types

That leaves wrist-pin locks if you’re going to use a free-floating wrist pin, which nearly all high-performance applications do. These are spring-type fasteners designed to provide an interference fit in a groove machined at the edge of each pin boss. The locks keep the wrist pin centered within the pin bosses while allowing for rotation. The elasticity of the lock allows them to be deformed in some manner for installation and removal.

There are three types used in automotive engines—snap ring or Tru Arc; Spirolock; and the wire lock or circlip, which is offered in at least three different designs. The last two styles are the most popular with performance engine builders.

Snap Rings

Generally Tru Arcs are the easiest to install and are more popular in lighter duty applications. The snap ring or Tru Arc is easily installed using dedicated pliers. The tips of these pliers fit into the holes at the ends of the snap ring. When the pliers handles are squeezed, the snap ring compresses enough to firmly seat into the retaining groove on the piston. A word of caution: snap rings are manufactured with a smooth and rough side. Be sure the smooth side faces the wrist pin.

Spirolocks

The Spirolocks—sometimes referred to simply as a spiral retaining ring—are constructed of flat stainless-steel wire wound into a spiral or small coil. They’re very effective at securing the wrist pins; but when stretched out for installation their sharp edges are exposed. “Spirolocks are the cheapest but are difficult to install and disassemble,” says Stevenson.

Many pistons require two Spirolocks on each side, doubling the installation time. There are probably as many different ways to install Spirolocks as there are engine builders. Using jewelers’ screwdrivers to dental tools, experienced mechanics have developed a number of personal tricks to avoid sliced skin as well as speed up the installation process. There are also some dedicated spirolock tools.

A Spirolock is installed by spreading it apart slightly. A leading edge is positioned inside the piston’s retention groove, then the coils are literally spun or walked into place inside the groove. Some engine builders prefer using their fingers, but most use one or two small flat-head screwdrivers to massage the spiral wire into the retention groove.

There are also dedicated tools such as the Lock-in tool from Precision Engine Service. It’s designed to install a Spirolock without having to handle the sharp edges. The Spirolock does have to be spread apart to fit in the grooves of the tool. The tool is positioned in the piston to start the leading edge of the Spirolock into the retention groove. The tool is then rotated counterclockwise until the Spirolock is properly seated in the groove.

Pins Designed For Lock Types

Although the three different types of wrist-pin locks are not meant to be interchangeable, the retention grooves machined for Spirolocks and snap rings are similar. Tru Arcs, or snap rings, and Spirolocks must also be used with wrist pins that have flat edges.

“The grooves are different shapes and dimensions, however Tru Arcs can be used interchangeably with Spirolocks of the same thickness,” says Stevenson.

Circlips, however, must be used with chamfered wrist pins. The retention grooves on the pin bosses must be designed with a small relief machined on the edge of the groove. Sometimes this relief or notch is used to help facilitate removal. Or it can be used to properly position a certain design of wire clip.

Tips and tricks for wrist-pin locks

- Regardless of the type of lock, make sure they’re properly seated and flush all the way around the retaining groove.

- Avoid scratching the piston with screwdrivers, O-ring picks or other tools. A deep ding can lead to a stress riser.

- Make sure the retaining groove is clean and free of grit that can prevent a proper fit.

- Some engine builders will deburr the ends of wire clips to ensure a cleaner seat in the retention groove.

- Make sure the pistons and rods are properly oriented before installing the pins. You don’t want to pull them apart because the rod chamfer doesn’t face the crankshaft fillet radius when the piston assembly is installed into the cylinder.

- Regardless of the style, wrist-pin locks are inexpensive, so the best policy is to never reuse them.

Getting Right with Wire Locks

“Wire locks are the best overall solution from a reliability standpoint as any side-to-side forces exerted by the pin serve to further seat the lock into its groove,” says Stevenson.

Wire locks are by far the most common lock type for high-performance pistons and come in three popular styles for automotive use (there are more that can be found in industrial and motorcycle engines). There’s the basic open-end clip that resembles a “C.” This lock can be installed with bare fingers or a mix of screwdrivers and picks, depending on the whims of the engine builder.

To assemble a full-floating piston and rod combo, first install one of the locks. Next, lube the connecting rod’s bushing and insert the wrist pin. The final step is installing the lock on the opposite side.

A modified version of the wire clip has up-swept tangs on each end that have a similar function as the holes on a snap ring. This allows a dedicated pliers for installation. This style is more popular with OEM applications than performance engines.

Engine builders generally develop a favorite style of wrist-pin lock over years of experience. Again, the two most popular with performance engines are the Spirolocks and wire clip or circlip. There is no research or data indicating that one is stronger or better designed than the other. It basically comes down to a choice by the engine builder. However, the piston manufacturer must be informed of this choice because the retention groove is machined differently and the correct wrist pin must be used.